I recently had the need to check a couple of puzzles that were geared towards intuitive solving, and consequently tricky to prove correct by hand. Luckily enough, Nikolai Beluhov posted an excellent Curve Data solver at just the right moment, allowing me to fix one broken puzzle. For the other, I took the chance to finally play around with logic programming. Prolog is likely the best-known language from this domain, but I went with Mercury, which is quite close to Prolog, but adds a couple of nice things like a static type system.

The project was quite successful: It solved the problem and was a lot of fun. Unfortunately, the solver turned out a little too complex to fit into a blog post, largely due to the complexity of the puzzle type. Thus, I decided to break it down to a way simpler (simplistic, even) puzzle, with the option of presenting the full solver in a second post.

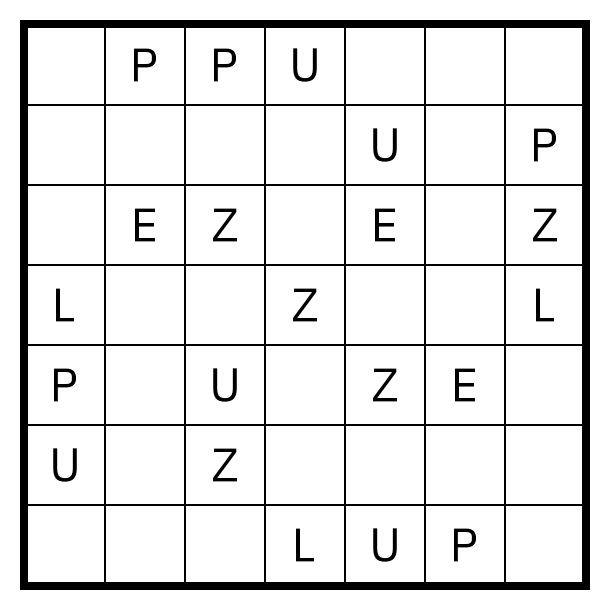

A word placement puzzle

Rules Write the word “PUZZLE” in the grid by placing letters in some empty cells. The word may read in any of the eight horizontal, vertical or diagonal directions.

Below, we’ll develop the solver step by step.

Building the solver

A brief disclaimer before we get started: I learnt all that I know about Mercury and logic programming from this one project, so it’s quite likely that I get some things wrong. If I come across as falsely authoritative below, I apologize. Any corrections much appreciated, as well as suggestions that would make the code more idiomatic.

My main sources were the excellent Mercury tutorial and the library documentation. There’s also some useful examples in the source distribution, which I found a little late. To run this at home, it looks like you have to compile Mercury from source, though Linux users may be lucky? Fortunately, it turned out to be quite straightforward to build.

The header

If you paste all the code from this post into a file wordplace.m (or download it from github), you can compile it with mmc --make wordplace, then run ./wordplace.

We start with a standard header section, which states that all we’re exporting is the main predicate, and which imports a bunch of modules from the standard library.

:- module wordplace.

:- interface.

:- import_module io.

:- pred main(io::di, io::uo) is det.

:- implementation.

:- import_module char.

:- import_module int.

:- import_module list.

:- import_module map.

:- import_module maybe.

:- import_module solutions.

:- import_module string.Types and data

Next, we define some types in order to be able to express the puzzle. We’re working with a two-dimensional square grid of characters; the puzzle is specified by the size of the grid, by the hints (characters at points), and the word we’re trying to place.

There’s no particular reason I went with named fields for size and a plain pair of integers for point here. They’re mostly the same, for our purposes at least. (There’s also an explicit pair type in the standard library (pair), don’t ask me why.) For word, we might have chosen string instead, but lists of characters seem easier to work with.

size and puzzle are both new types, with the difference that the fields are named for size, the others are just new type names. There’s no need for the the left “puzzle” (the type name) to agree with the right “puzzle” (the data constructor).

:- type hint == {point, char}.

:- type word == list(char).

:- type size ---> size(width :: int, height :: int).

:- type puzzle ---> puzzle(size, word, list(hint)).Our sample puzzle is then simply a constant function with no arguments, with value P of type puzzle constructed from its parts.

:- func sample = puzzle.

sample = P :-

S = size(7, 7),

W = string.to_char_list("PUZZLE"),

Hs = [ {{1, 6}, 'P'}, {{2, 6}, 'P'}, {{3, 6}, 'U'}

, {{4, 5}, 'U'}, {{6, 5}, 'P'}

, {{1, 4}, 'E'}, {{2, 4}, 'Z'}, {{4, 4}, 'E'}, {{6, 4}, 'Z'}

, {{0, 3}, 'L'}, {{3, 3}, 'Z'}, {{6, 3}, 'L'}

, {{0, 2}, 'P'}, {{2, 2}, 'U'}, {{4, 2}, 'Z'}, {{5, 2}, 'E'}

, {{0, 1}, 'U'}, {{2, 1}, 'Z'}

, {{3, 0}, 'L'}, {{4, 0}, 'U'}, {{5, 0}, 'P'}

],

P = puzzle(S, W, Hs).We’ll also need some way to represent the character grid. Here, we’ll go with a map of point to char. A cell is empty if the corresponding point is not in the map, otherwise the character in that cell is the mapped value. We also include the size of the grid, and agree to index the cells with pairs {0..width-1,0..height-1}.

:- type grid ---> grid(size :: size, map :: map(point, char)).An outline, and main

Now we’re ready to declare the core of our solver:

:- pred solve(puzzle::in, grid::out) is nondet.solve(P, G) states that the grid G is a solution of the puzzle P. Futhermore, we’re saying that we’ll give a definition of solve that allows determining such G given P (the in and out modes), and that for a given P, there may be 0 to many G (nondet).

The fun part will be implementing solve, but first let’s wrap it in a proper program. Our aim is simply to find and print all solutions to the puzzle. Printing is handled by a deterministic predicate print_grids (implementation deferred), which takes a list of grids, and transforms the state of the world (which has type io). Compare to the declaration of the main predicate in the header.

:- pred print_grids(list(grid)::in, io::di, io::uo) is det.The solutions module provides some tools for getting at all results of a predicate. solutions.solutions in particular returns all outputs of a one-parameter predicate. Now we can define main:

main(IO_in, IO_out) :-

solutions(pred(G::out) is nondet :- solve(sample, G),

Gs),

print_grids(Gs, IO_in, IO_out).The first argument to solutions is an anonymous predicate that’s the partial application of solve to our sample puzzle.

This is probably a good point to think about how to think about that definition of main: We’re not saying to first compute the solutions, afterwards print the grids. Instead, we’re saying that the predicate main is the conjunction of the two statements, the comma should be read as “and”. We leave it to the compiler to actually do something with that definition.

main transforms the state of the world from IO_in to IO_out if and only if Gs is the list of solutions to our puzzle, and printing the grids Gs transforms the world from IO_in to IO_out. Now running the program means finding out what main does to the state of the world, which means finding out what print_grids does, which depends on Gs. So solutions needs to be “called” first, before print_grids can be “called” on the results.

In particular, the order of the statements doesn’t matter, we might as well have placed that print_grids statement at the beginning. That said, it’s helpful to order definitions in a way that they can be evaluated top-to-bottom.

Solving the puzzle

We’ll let the grid do most of the work. First, let’s set it up properly, by setting the size and initializing the underlying map.

:- pred init_grid(size::in, grid::out) is det.

init_grid(S, G) :-

map.init(M),

G = grid(S, M).Some bounds checking will be useful. Note that the following two predicates are in a sense the same: They both state that the point P is within the bounds given by S. But as defined below, in_bounds tests this property, while nondet_in_bounds generates points within the given bounds.

:- pred in_bounds(size::in, point::in) is semidet.

in_bounds(S, {X, Y}) :-

X >= 0,

Y >= 0,

X < S^width,

Y < S^height.

:- pred nondet_in_bounds(size::in, point::out) is nondet.

nondet_in_bounds(S, {X, Y}) :-

size(W, H) = S,

int.nondet_int_in_range(0, W - 1, X),

int.nondet_int_in_range(0, H - 1, Y).With this, we’re ready to define the fundamental grid operation, placing a character C at a point P in a grid G. This is semi-deterministic: If the position is out of bounds, or if there’s already a different character at that location, the character can’t be placed. Otherwise, the resulting grid is unique. In other words, there’s at most one result.

:- pred place_char(point::in, char::in, grid::in, grid::out) is semidet.

place_char(P, C, Gin, Gout) :-

grid(S, M) = Gin,

in_bounds(S, P),

map.search_insert(P, C, OldC, M, M1),

(

OldC = no

;

OldC = yes(C)

),

Gout = grid(S, M1).Line by line, we first deconstruct the input grid, then check that the point is in bounds. We rely on map.search_insert to handle the conditional map update. Its input parameters are the point P, the character C, and the original map M. Its output consists of OldC which has type maybe(char), and the modified map M1. A maybe(char) is either nothing (no) or some character (yes('a')). Now search_insert does one of two things: If the map already contains P with value D, the map isn’t changed, and OldC is set to yes(D). Otherwise, the element is inserted, and OldC is set to no.

Following the optional insert we see a disjunction: We say it’s fine if OldC is no (i.e., the cell was previously empty), or if OldC is yes(C) (i.e., the cell was previously occupied, but with the character we’re trying to place. The case that we’re deliberately omitting is yes(D) for some other character D: that’s a real collision.

Finally, we put S and the modified map M1 back together to yield the result grid.

Building on this, we can define a couple of predicates to place more than one character at a time. First, a list of located characters (we could use foldl here instead of explicit recursion).

:- pred place_chars(list({point, char}):: in, grid::in, grid::out) is semidet.

place_chars([], Gin, Gout) :-

Gout = Gin.

place_chars([{P, C}|Xs], Gin, Gout) :-

place_char(P, C, Gin, G1),

place_chars(Xs, G1, Gout).Next, placing a word in a specified direction starting at a given point.

:- type dir == {int, int}.

:- func move(dir, point) = point.

move({DX, DY}, {PX, PY}) = {PX + DX, PY + DY}.

:- pred place_word(point::in, dir::in, word::in,

grid::in, grid::out) is semidet.

place_word(_, _, [], Gin, Gout) :-

Gin = Gout.

place_word(P, D, [C|Cs], Gin, Gout) :-

place_char(P, C, Gin, G),

P1 = move(D, P),

place_word(P1, D, Cs, G, Gout).Or placing a word in an arbitrary direction at an arbitrary point:

:- func dirs = list(dir).

dirs = [ {-1,-1}, {-1, 0}, {-1, 1}, { 0, 1}

, { 1, 1}, { 1, 0}, { 1,-1}, { 0,-1}

].

:- pred place_word_any(word::in, grid::in, grid::out) is nondet.

place_word_any(W, Gin, Gout) :-

grid(S, _) = Gin,

nondet_in_bounds(S, P),

list.member(D, dirs),

place_word(P, D, W, Gin, Gout).Puzzle solved:

solve(Pz, Gout) :-

Pz = puzzle(S, W, Hs),

init_grid(S, G0),

place_chars(Hs, G0, G1),

place_word_any(W, G1, Gout).Printing the solutions

To finish off the program, we still need to implement print_grids. That’s below. with some code that feels a little suboptimal. I’m sure it’s not necessary to define ranges of integers, and there must be a more elegant way to convert from a semi-deterministic predicate to a maybe type than going through lists. But it works. Edit Improved version, thanks to Paul Bone.

By the way, the !IO is just magic syntax for stringing through a list of modifications, we might have used !G at some points above where we did the Gin, G1, Gout dance.

:- func int_range(int) = list(int).

int_range(N) = (if N =< 0 then [] else [N - 1|int_range(N - 1)]).

:- pred char_at(grid::in, point::in, char::out) is semidet.

char_at(G, P, C) :-

C = map.search(G^map, P).

:- func show_char(grid, point) = char.

show_char(G, P) = C :-

( if char_at(G, P, CPrime) then

C = CPrime

else

C = ('.')

).

:- func show_line(grid, int) = string.

show_line(G, Y) =

string.from_char_list(

map(func(X) = show_char(G, {X, Y}),

list.reverse(int_range(G^size^width)))

).

:- func show(grid) = list(string).

show(G) = map(func(Y) = show_line(G, Y), int_range(G^size^height)).

:- pred write_line(string::in, io::di, io::uo) is det.

write_line(L, !IO) :- io.format("%s\n", [s(L)], !IO).

print_grids([], !IO).

print_grids([G|Gs], !IO) :-

foldl(write_line, show(G), !IO),

print_grids(Gs, !IO).